This site hasn’t been updated since 2012. You can still peruse who I was back then, but know that much of what I think, feel, write, and do has changed. I still occassionally take on interesting projects/clients, so feel free to reach out if that’s what brought you here. — Nishant

I have decided to leave Microsoft and go out on my own.

I'm interested in building a product and I've registered Minky to help me do that. Honestly, that's all I've got right now.

Really, I want to talk about Microsoft today. Leaving a company after 5 years is a big deal. We spend more time at work than we do with family and friends. Leaving without saying a word just feels wrong.

So, here goes.

If you've read anything I've written in the past couple of years (or have recently attended one of my talks), you probably already know that I'm somewhat obsessed with topics related to the brain. I tend to spend a lot of my free time reading about error analysis, cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, neuroscience, and the likes. I've even shared a reading list to that end with you in the past.

There was one particular study I came across a few years ago in a book by Kathryn Schulz, Being Wrong, that changed how I think at a foundational level. The study, known as the Sally-Anne Test, remains one of the most cited — and in the context of autism, still fairly controversial — developmental psychology studies in existence.

The Sally-Anne test is administered to children between the ages of three and four. It involves staging a simple puppet show involving two characters, Sally and Anne. Sally places a marble in a basket, closes its lid and leaves the room. Shortly thereafter, the very naughty Anne, enters the scene, flips open the lid of the basket, pulls out the marble and places it in a box sitting in the corner. Now, the child who has witnessed all of this, is asked a simple question —

When Sally returns, where will she look for the marble?

Almost every child in this age group exclaims with confidence, "In the box!" This answer is baffling to adults for the obvious reason: there's no way Sally could have known that the marble was mischievously displaced by Anne because Sally wasn't around to witness that. But the children don't care about this detail. To them, reality and their minds' representations of reality are one and the same. Sally thinks the marble is in the box because, well, it is in the box.

The children provide an incorrect answer because they have yet to develop what is known as the representational theory of mind, what is considered a key differentiating feature of human beings as compared to most other mammals. Theory of mind is what bestows upon us the knowledge that our mind's version of reality isn't true reality, but an interpretation of reality. Furthermore, it gives us the knowledge that everybody has their own mind and thus, their own reality.

But what, pray, does this have to do with my departure from Microsoft? It's a good question and one I will answer with another question —

What is the most important thing I am taking away from Microsoft?

Turns out that that's the $64,000 question you have to answer for yourself when you spend approximately 10,000 hours of your life working at a company.

10,000 hours. Wow.

I came to Microsoft because I was (and still am) interested in designing and building software products. I joined the company fresh out of a two-year stint as a Program Manager at Amazon, the brunt of which was spent surviving an epic death march towards the launch of Amazon's 35th product category: Instant Video (back then known as Unbox). It's easier to recount what went well on that project because there wasn't much. Upon shipping the first version over a year behind schedule — a schedule that was my responsibility, but mostly out of my control, I might add — over 90% of the team quit not just the Unbox team, but the company. I was one such statistic as well.

Now, if you were to ask me to list the causes for the failure that was the initial product, the response would have been at the tip of my tongue. I'd have immediately furnished you with an exhaustive list: weak product vision, collective lack of engineering and design experience, lack of process, competing political agendas, lack of leadership, too many cross-functional dependencies, and so on. Simply put, I'd have painted you a picture of what we fondly refer to in the industry as a clusterfuck.

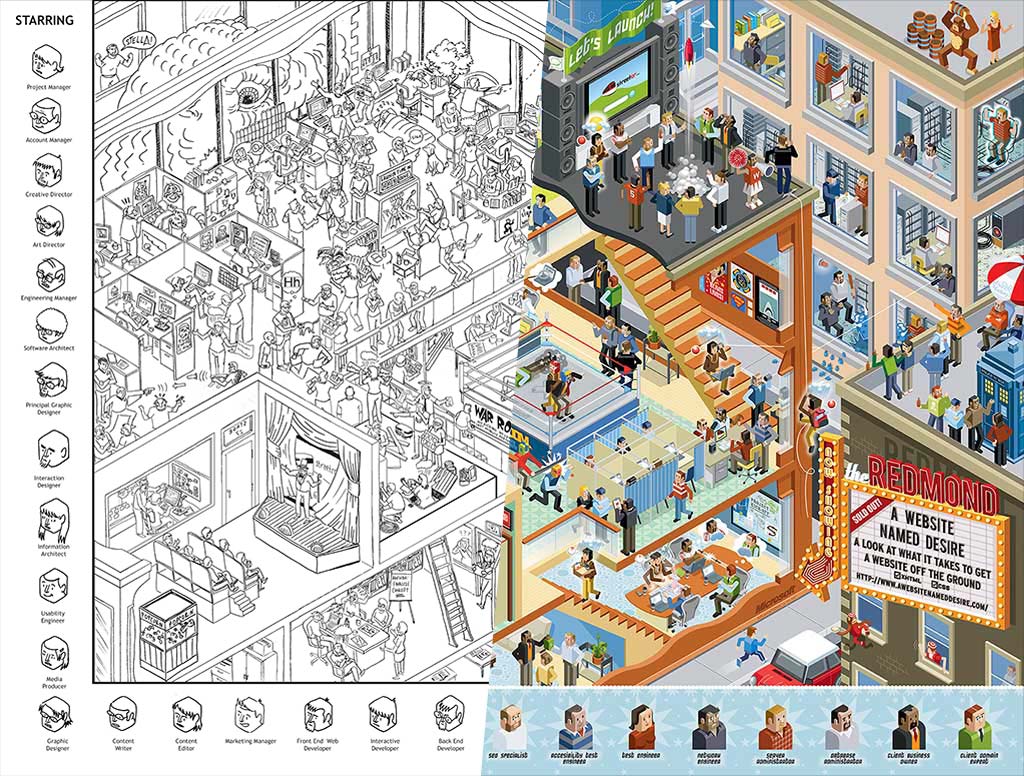

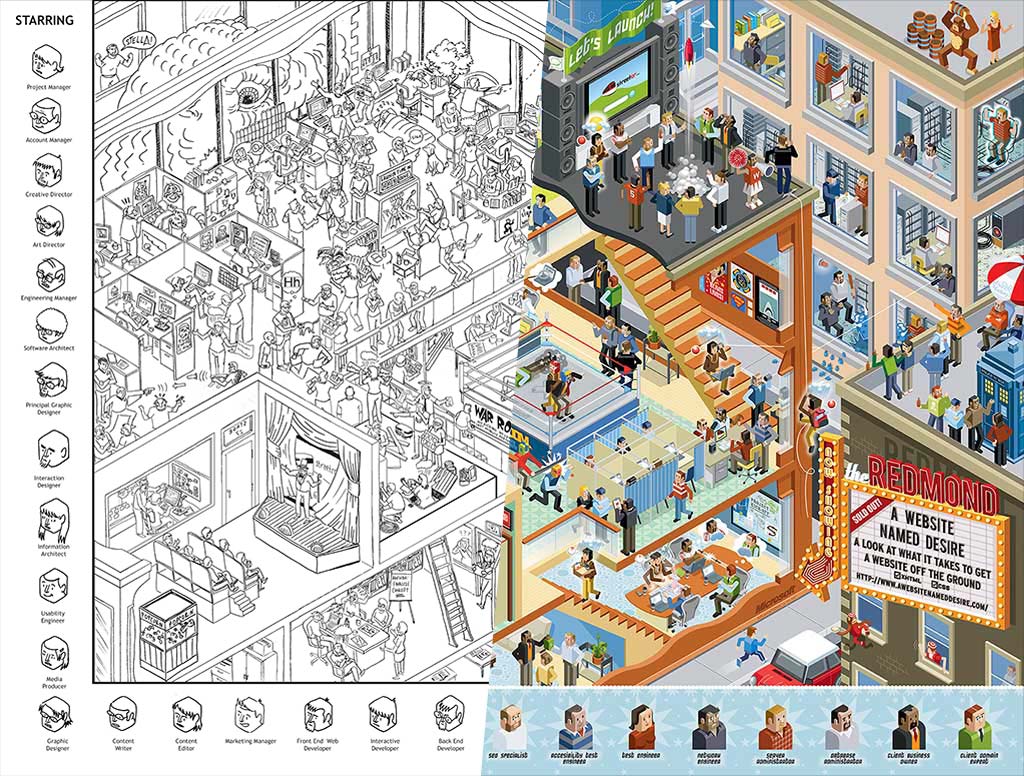

Speaking of, one of my first projects at Microsoft was A Website Named Desire. A colleague of mine, Erik Saltwell, and I came up with this idea for a poster that illustrates what goes into getting a web application off the ground. It was based on some fantastic research Erik had done for the now discontinued Expression Web. We hired XPlane to help us realize our vision: one that took hundreds of painstaking hours of illustration and creative reviews.

Our goal was to illustrate the typical software product development cycle in practice — non-linear, highly chaotic, angst ridden, tear-jerking — in stark contrast to the apparently neat, linear, and highly theoretical ones typically presented in software project management literature. Actually, if you follow the project manager in the poster (hint: she's the one with a little progress indicator next to her head and a look of perpetual resignation on her face), you will see the theoretical linearity of the process hidden in the chaos.

A Website Named Desire turned out to be a hit campaign. We printed and distributed over 10,000 posters, and I like to think it was a hit because most people who saw it instantly related to the picture of dysfunction it painted. But as good as the poster was at illustrating the "how" and the "what", it barely scratched the surface of "why". Why is the act of building software — and more importantly, life itself — often such a clusterfuck?

Pretty much everything we need to know about the root causes of, not just software project failures but most failures in life, can be traced back to the Sally-Anne test. As we get older we develop and refine our theory of mind allowing us to understand and deconstruct extremely complicated situations. And with a little help from our friends like mirror neurons, we are literally able to feel what others feel. Even when we are convinced about something, we acknowledge that the conviction may not be a fact. Nothing illustrates this aspect of our existence better than the adage, "If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?"

But this doesn't stop us from having very strong convictions. And our ability to be fully convinced about something while acknowledging our own fallibility at judging anything is an elegant imperfection that suspends us in a confusing duality — we know that we can't know anything with 100% certainty, except certain things are 100% certain to us. It is a duality that escapes our consciousness most of the time because our sanity depends on it.

It is why we know that murder is always wrong. Or that Microsoft is evil while Google isn't. Or that banning same-sex marriages is the will of the Almighty. Or that JavaScript programmers aren't real programmers. Or that the right to bear arms is at the root of violent crimes. Or that ______ is smart/good/wise/credible/trustworthy and ______ isn't. Or that racism or sexism don't exist. Or that Instagram made a deal with the devil. Or that some of us are born into a lower caste than others. Or that Apple is perfect.

Our list of views is endless, and what's more is that for every view we hold, there's someone who holds an opposing view with the same level of conviction. And collectively, our views cancel out and we fail the Sally-Anne test much like our toddler selves: a hypothesis that may as well be a binding law of physics at this point thanks to the work of folks like Dan Ariely and many before him.

So where does this leave us? Actually, where does this leave me in relation to my most important takeaway from 10,000 hours spent at Microsoft? OK, I'll spit it out now.

Certainly, I learned a tremendous amount about how (and how not to) design, build, ship, and market software products. If my Work page is any indication, I acquired a boatload of new skills and got to practice honing others. But I got much of that at Amazon, too, and it's something one would expect from most decent jobs. What was different is that — through the sheer act of finding a voice at a controversial company like Microsoft with millions of customers, fans, and critics — I stumbled upon the most important aspect of building products: people. And not in that awfully tired way repeated by folks who talk about how "it's all about the people" but never really practice it. I realized it in the kind of way that I can only compare to the final scene of the Matrix where Neo sees the agents as strings of code.

This is not to say that I can fly around the Matrix and bend will. Rather, it's that I can see and understand things that escaped me years ago when I was at Amazon. I was convinced of the causes that led to the failures of Unbox. But in hindsight, they were merely symptoms of other, more elusive root causes. Now, if my old self were here, he'd say, "Of course they were symptoms. The real problem has always been the people." But he'd say it in that awfully tired "people are the source of the problem because they are evil or stupid or both" way.

I now exist in a context where most things can be explained without the use of adjectives like evil and stupid. And with some creativity and knowledge of human behavior, I believe most crises can be averted long before they amount to train wrecks. I even give talks about this. Simplistic black or white (evil and stupid) explanations are tempting and the forté of, as Daniel Kahneman dubs it, System 1 mode of thinking: the automatic brain. But as Einstein put it, "Make things as simple as possible, but not simpler." Even the simplest analysis of human behavior maps to some shade of gray, not black or white, and requires the critical thinking offered by System 2. And, in no small part due to the opportunities I received at Microsoft, I learned to see and paint with grays. In a Sixth Sense like twist of fate, I learned the "Why?" of A Website Named Desire.

The best part of it all is that I also came face-to-face with and embraced a reality most people aren't fortunate enough to truly discover in their lifetimes: my mind's version of reality will never equal true reality. And no amount of knowledge or experience will likely ever make it so.

10,000 hours well spent, if you ask me.

comments powered by Disqus