This site hasn’t been updated since 2012. You can still peruse who I was back then, but know that much of what I think, feel, write, and do has changed. I still occassionally take on interesting projects/clients, so feel free to reach out if that’s what brought you here. — Nishant

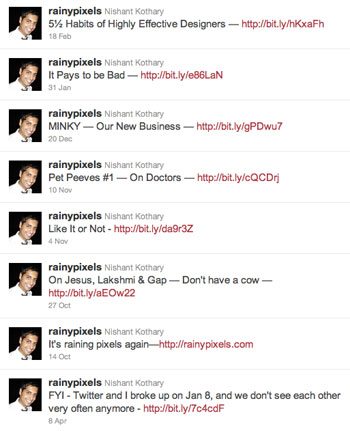

I broke up with Twitter just over a year ago—on January 8, 2010.

I use the phrase "broke up" literally. After all, my departure came complete with a ‘Dear John' letter titled, Dear Twitter. By posting this publicly I'd finally committed to ending a tumultuous relationship. And boy, did I. I quit cold turkey and have stayed clean since then.

So, let's get right to the $64,000 question—Was it worth it?

As with most answers to $64,000 questions, a simple "yes" or "no" answer won't suffice (it's a "yes", by the way). The interesting part isn't the answer itself, but, as they say, the journey.

There exists considerable and justifiable concern today about Twitter's resemblance to a drug.

Indeed, Twitter addiction is a serious and growing problem that's even making cameos in Hollywood. And, it's a particularly elusive addiction in that there are no obvious symptoms or side-effects. Like say, abusing Twitter generally doesn't provoke one to discuss philosophy with a cat.

To make matters worse, diagnosing a Twitter addiction is one big hit-or-miss charade. What does it mean to be "addicted"? If you can stay off Twitter for a day, does that mean you're not an addict? Or is it a week? What if you just peruse, but never send tweets?

My hindsight indicates that trying to determine addiction criteria is a waste of time. Each individual has a unique motivation guiding his or her Twitter usage, and the physical manifestation of the addiction varies significantly as well. Scoble tweets tens of times an hour, for instance, but that doesn't mean he's addicted (I'll argue later that he may be quite the opposite of addicted). On the flipside, I'd reduced my tweeting frequency to one per day towards the end, and I still felt horribly shackled.

The clue to figuring out what it means to be addicted to Twitter comes from a celebrated yet unexpected book—yes, life after Twitter indeed includes all sorts of crazy things like books!—written two decades ago by a Hungarian psychology professor, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Titled "Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience", Mihaly shares in his book the secret to happiness, a concept he calls, you guessed it, flow.

So, what is flow?

In Mihaly's own words from a Wired Magazine interview, "Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost." Anyone who has pursued a hobby all their life—like playing the guitar, running, writing, cooking, solving puzzles, even reading—should find it pretty easy to relate to this.

According to Mihaly's research, the key aspect to achieving flow is our ability to control our consciousness and immerse it activities that are autotelic, i.e. activities that are self-contained and done without the expectation of some future benefit, but simply because the doing itself is the reward.

The common motivation behind using Twitter, however, is exotelic, i.e. extrinsically motivated. On Twitter, we seek validation, role-play, try to score followers, indulge in lekking, promote ourselves and our work, promote others in hopes that they'll promote us, and indulge name-your-favorite-exotelic-motive. This is not to say that any of these motives couldn't manifest autotelically—take Scoble who turned the activity of growing a follower count into an endurance sport; Mihaly interviewed many long-distance athletes and found them to be in a high flow league—but few of us have succeeded at making them autotelic.

It's not just that we engage exotelically, but the inevitable infinite loop of it all that's most worrisome. Twitter has the ability to gain control of our consciousness. That is, Twitter diminishes our attention span drastically. The more we are on it, the more we seem to want it. When we're away from it, we spend our time thinking about it. And, the evidence echoes in the familiar gripes of countless Twitter users who describe their social media involvement with terms usually reserved for codependent love affairs.

But, it's unclear whether overuse of Twitter has any lasting physical or mental effects; we certainly haven't gotten to the point that WoW gamers did a few years ago. But as most people who speak of Twitter as an infatuation already suspect, the price of the habit is opportunity cost. Twitter may not make you do crazy things, but it may make you stop doing many things.

There's nothing like a year's worth of experiences to confirm this suspicion.

I made a quick list of things I did in 2010 that I felt went above and beyond prior years. They may not be big to others, but they were significant for me. Bear with me as this list is a means to an end.

I designed and launched a personal blog, started training for and competing in triathlons (ironically, this was before I read Flow and its findings about endurance athletes), launched a small company/side-project with my wife, wrote around 15 articles, and read around thirty books (the sum total for the two years before it was, embarrassingly, two books). This was in addition to doing really well at my job, which is a time commitment in and unto itself.

It's also worth noting that 2010 was also a particularly relaxing and stress-free year for me. I took two vacations (a total of three weeks), hosted family at my house for around eight weeks (this is borderline insane, and I don't recommend it), started taking ski-lessons, and even watched all the seasons of Prison Break and 24 on Netflix. OK, the last one wasn't exactly relaxing or a healthy substitute for Twitter because we were addicted to both shows and watched them in marathon fashion till our brains went numb (the astute among you notice a trend here—I have a propensity to surrender my consciousness to mindless entertainment).

All of these activities share one thing in common—they require focusing one's attention for long periods of time—something I couldn't dream of doing in my Twitter days because, well, I had the attention span of an oyster.

Admittedly, correlation is not causation, and my higher productivity levels likely have to do with many other factors—hormonal changes, better financial stability, exercise-induced endorphins, excessive Weimaraner petting, and so on. But correlation is correlation, and I've found a strong, almost causation-like relationship between quitting Twitter on one side and higher productivity levels and stronger personal relationships on the other.

So, we're clearly concluding that quitting Twitter can be a very good thing. But that's not the $64,000 question anymore, is it?

There's a much bigger question on our minds—a natural, deeper, even philosophical, question.

Is Twitter bad?

It turns out that we can convincingly argue both sides on this one. And, we have—Packer and Carr are just one example of the case in point. Depending on which way we swing, we tend to pick one or the other. And then a very elegant human imperfection, confirmation bias, steps in to fortify our choice. We are wired to pick and then protect our binary choices—red or blue—so much so that it's the foundation for everything from our computers to our political process.

In a broad sense, this question we're trying to answer is not as much about Twitter as it is about the paradox that is life itself. It's a dilemma that has vexed us through the ages as evidenced by the old saying, "One man's meat is another man's poison." But if my recent experience reinforced anything, it's that the answer to such trick questions often lies somewhere on the spectrum between red and blue. The real answer is a shade of purple, which coincidentally, is the color of introspection.

So if we must have an answer to the question whether Twitter is bad, then let it be this—you must find the shade that helps you achieve flow. One where you're in control, not Twitter.

As for me, it seems I'm ready to give Twitter a second chance myself a second chance with Twitter.

comments powered by Disqus